The Myth of the Corner Store

Why zoning isn’t what’s holding back corner grocery stores or 15-minute neighborhoods.

For decades, planners have envisioned small, pedestrian-friendly commercial hubs within residential neighborhoods. A local café, a small grocery store, or a retail shop embedded in a walkable area where people can meet their neighbors and run errands without driving. This concept is central to the growing 15-minute city movement, which aims to create neighborhoods where residents can access daily essentials—jobs, schools, parks, groceries—within a short walk or bike ride.

As a leader in progressive planning policies, Oregon‘s statewide land use planning program embraced this vision as early as the 1970s. The Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC) adopted the first 14 Statewide Planning Goals in 1974. Goal 9 mandated that local governments ensure adequate land availability for various economic activities essential to the well-being of Oregon citizens. This includes planning for commercial developments that serve local communities. Goal 12 required cities and counties to develop Transportation System Plans (TSPs) that promote public transit, biking, and walking as alternatives to car travel. It also encourages compact, mixed-use development to reduce travel distances. Nearly a quarter century ago now, ODOT and DLCD released the Commercial and Mixed-Use Development Code Handbook. So these ideas are far from new.

These statewide planning goals and best practices led many municipalities to zone some corner lots and corridors as neighborhood commercial and mixed use districts with the expectation that, as density increased, small businesses would emerge to serve local needs.

More recently, Oregon‘a Climate Friendly and Equitable Communities rules eliminated parking minimums in areas within a half-mile of frequent transit, making it easier to build housing and commercial uses without dedicating space to cars. Planners hope these changes will help create the walkable, mixed-use communities they have been designing on paper for decades.

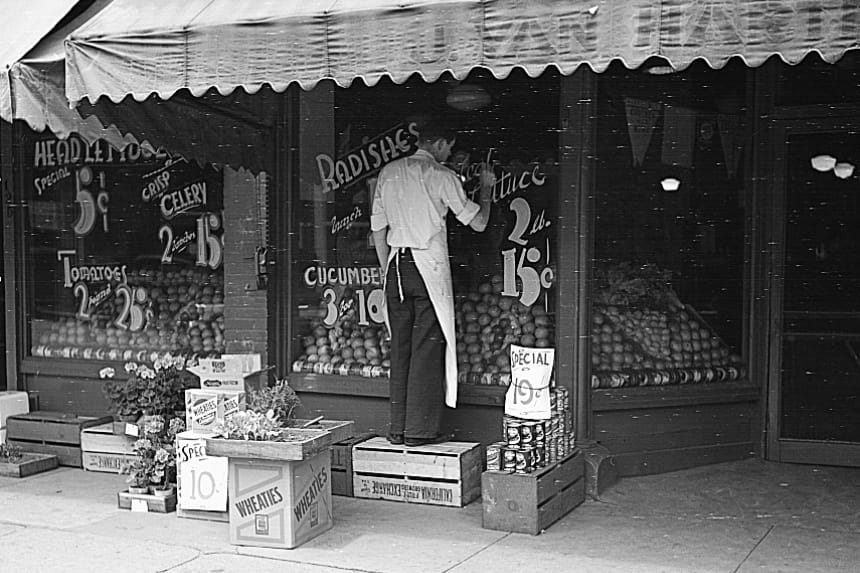

Yet, despite these efforts, the small corner grocery store remains elusive. While convenience stores persist and often are the only source of food accessible by foot in many neighborhoods, these establishments don’t typically offer many healthful food options. Pricing can also be predatory. Absent a gas station or convenience store, land designated for commercial uses can sit vacant for years and is sometimes rezoned for housing when the market fails to support retail. Former residential districts rezoned for commercial can even limit what homeowners can do with their legal, non-conforming residential buildings while communities wait for commercial uses that may never materialize. The disconnect between zoning theory and economic reality is stark.

The Economic Shift

The failure of small-scale retail to materialize is not simply the result of zoning or a lack of density. It is the product of larger economic forces that have made neighborhood commercial development difficult to sustain.

For much of the twentieth century, small grocers and independent retailers thrived because they occupied a secure place in the supply chain. That changed when antitrust laws like the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936 were weakened, allowing big-box retailers to negotiate bulk discounts that independent stores could not match. Large grocery chains expanded. E-commerce reshaped shopping habits. Many daily errands that once required a short walk to the store now happen through delivery services or at a supermarket on the drive home.

Even in neighborhoods that could theoretically support small-scale retail, developers hesitate to build it. A café or market must survive on razor-thin margins while competing with national supply chains and online convenience. Meanwhile, housing remains a far safer investment, making it the default choice for vacant commercial parcels.

Retrofitting the Suburbs

The 15-minute city movement has gained traction as planners and advocates push for more complete neighborhoods. However, transforming suburban areas built for cars into walkable communities is not an overnight process. Decades of land use decisions have prioritized large-format retail and auto-oriented infrastructure, making it difficult for small businesses to compete. Neighborhood-scale retailers no longer develop their own buildings but instead rely on the market of existing commercial real estate, which has increasingly become centralized in large shopping centers or in auto-dominated strip malls, sometimes far from transit.

Even in places with progressive zoning policies, many of these barriers persist. Developers often lack financial incentives to take a risk on small retail. Many communities remain tethered to a suburban pattern of development that cannot be undone with zoning reform alone.

Developers sometimes pay lip service to the commercial requirements of mixed use properties in order to gain certain incentives. For example, by providing a small retail space, a developer might gain tax advantages or density bonuses knowing that it may ultimately be used as a leasing office or live-work unit it if goes unleased for a neighborhood oriented commercial use.

This process will take time. Planners working in established suburban areas recognize that meaningful change may take decades. While cities and counties can remove barriers and create more flexibility, true mixed-use, walkable communities will require a broader shift in economic policy, infrastructure investment, and consumer behavior. Finally, it will take bold and creative action from transit and other land-owning public agencies to forge public-private partnerships that prioritize creating places worth caring about instead of places for people to park their cars.

Why Zoning Alone Won’t Fix This

For all the focus on zoning reform, the economic structure that once made corner stores viable has largely disappeared. The elimination of parking minimums and the expansion of mixed-use zoning have eliminated most land use barriers for developers, but these tools alone cannot create a market where one does not already exist.

If cities want to bring back neighborhood-scale retail, they will need to do more than zone for it. They will need policies and incentives that actively support small businesses. They will need to rethink the structural advantages given to large retailers. They will need long-term investment in transit and pedestrian infrastructure.

Until these shifts happen, the corner store will remain an idea that planners and urbanists believe in, but one the market does not.